Adoption Often Doesn’t “Save” a Child

Mila Konomos says that if you help the family, you help the child

ADOPTION SERIES | PART THREE OF FIVE

For a recent article I wrote about manipulative adoption industry language (“The ‘Loving Option’ Is a Lie: How the adoption industry uses language to mislead and manipulate”), I interviewed five women: two adoptees (Lina Vanegas and Mila Konomos), two birth — or first — mothers (Renee Gelin and Amy Seek), and one adoptive mother (Diana). This five-part Adoption Series will comprise segments of our interview transcripts that didn’t appear in the story.

This third interview in the series is with Mila Konomos, who was six months old when a White military couple adopted her from a Christian agency in Seoul, South Korea. Her profile on Instagram, where as @the_empress_han she offers support to adoptees while advocating to abolish adoption, reads, Adoption Survivor, Mail Order Daughter, Poet.

KT: I used to wonder, “What if I got pregnant and couldn’t get an abortion? Would I put it up for adoption? Could I put it up for adoption?” But I never thought about the adoptees’ perspective until I recently came across an #adopteevoices conversation on X. I’m new to this, so if I ask you anything offensive, I deeply apologize.

MILA KONOMOS (MK): I never assume that people know. This is one of those systems of oppression that’s been so thoroughly colonized that most people I encounter have no idea. The dominant narrative is called the dominative narrative for a reason. So I’m not shocked or surprised that most people don’t know.

In my own journey I was a poster child for adoption for the first half of my life, so I’m not going around judging everyone like, I can’t believe you think this. Like I said, the narrative is strong. It’s propaganda. And the reason it’s propaganda is because it works.

I was a poster child for adoption for the first half of my life…The narrative is so strong. It’s propaganda. And the reason it’s propaganda is because it works.

KT: Do you say you were adopted or do you use “bought” and “sold”? Do you have a preferred language?

MK: Some people have issues with the word “adoptee” because it’s like “employee;” it implies that we received some kind of benefit from it. I refer to myself as an adoption survivor.

I do use the word “adoption.” I know other adopted people who refer to themselves as sold and bought, and I think that is important, as well. Because adoption is such a unique oppression, I choose to still use it. It’s important to distinguish it from other forms of oppression. But that’s why I also use language like “survivor” or “trafficking” or being “sold” and “bought.”

KT: In your interview on the podcast Adoptees Crossing Lines, you talk about your experience with “Orphan Sunday” [a Sunday designated by churches to raise awareness of, and encourage, adoption]. When you were a child looking out at your parents and at the congregation, who expect you to say certain things, did you believe what you were saying? Or, if you didn’t, do you remember what it felt like standing there?

MK: These were things I was saying as a teenager, but also as an adult. In my college years, I was—with my co-leader — basically running and facilitating a campus ministry, so there were events where I was speaking in front of thousands of people. And I did believe it at that time.

But I also believed that it was painful being an adopted person. I had so, so many struggles, but I wasn’t allowed to talk about that. There was an event where they were trying to recruit prospective adopters, and I had written up a little speech because I had been asked to share at this event, and I got censored. It was like, “Nope, you’re not going to talk about that.”

It was painful being an adopted person, and I had so, so many struggles, but I wasn’t allowed to talk about that

It wasn’t even like I went into great detail. I just shared how I’d struggled with depression and with feeling like I don’t belong, basic things like that. But it was like, “That may discourage adopters from wanting to adopt.” The mentality was, “We need to sell this. We need to get as many people as possible to adopt.”

I did believe the propaganda, and I had to internalize it because that was all I had known up to that point. But it was complicated, because I also knew what my lived experience was telling me: that it wasn’t all cake and roses.

I didn’t feel safe to question it out loud. Anytime I did, I got my hand slapped by the church, or by my family or friends, or whoever was in my life at that time, because at that time I was immersed in the culture of, “Adoption is beautiful. Adoption saved you. You’re lucky. You’re fortunate.” There was just one side of the multifaceted experience that I was allowed to give space to.

I was immersed in the culture of, “Adoption is beautiful. Adoption saved you. You’re lucky. You’re fortunate.”

It wasn’t until getting more out on my own and getting away from all of that that I was able to finally start to deconstruct it and really start my decolonial journey.

KT: Your parents already had children when they adopted you. Why did they adopt?

MK: My adoptive mother was initially married to someone, and she did experience fertility issues and miscarriages. My oldest brother is actually from the Baby Scoop Era. He was born in the 1960s and was adopted by my adoptive mother and her first husband. Her first husband unfortunately died in the American War in Vietnam, and about a year later, she met the guy who was my adoptive dad, and they got married. He was in the Navy, too, a naval officer. Six weeks later they had to move to Japan and were living on a military base there in Yokosuka.

They had the two children — an adopted son, and then my mom’s biological son from her first marriage — and they really wanted a daughter. Because of my mom’s history with fertility issues and miscarriages, they were like, “This is a great way to get a girl.” This was in the mid-1970s, when adoption was really peaking in Korea.

With the history of Japan occupying and attempting to colonize Korea, there was that kind of situation there, so they traveled to Korea from Japan. And this is how it’s so clearly trafficking: My dad at that time was considered a high-ranking American military officer, so because of colonialism and American occupation, when they got there it was like, “We need to present them with a product immediately.” So they start looking through a catalog [of children to adopt], and I was brought in, like, “Here. We have someone for you already.” But I mean, it’s just — again, they literally had catalogs of children.

KT: How did you come to be there?

MK: My papers were fabricated. It was said that I had been abandoned and that I was adoptable. I had not been abandoned. I was not an orphan. As far as how I was bought, I think it was because there was a very well-established adoption industry between America and Korea.

There’s a paper I always encourage people to read on the origins of Korean adoption called Cold War Politics and Intimate Diplomacy. It’s a free PDF that really explains the geopolitical context of it.

My papers were fabricated. It was said that I had been abandoned and that I was adoptable. I had not been abandoned. I was not an orphan.

That’s another thing about adoption: Because of the way it’s been propagandized, people view it like it’s apart from politics, and like it’s this anecdotal, case-by-case situation, like, “Oh, there’s this mother in distress or this family in distress, and here’s this White savior family. They’re here to save this situation.”

But if you zoom out and really look at how all of this happened, it’s rooted in American or Western invasion and war, and disrupting a country for their resources. Not just physical, but political and economic, and Korean adoption is really where that process became codified, in a way.

Of course there were the orphan trains and obviously the disruption of indigenous communities, and it’s all an extension of that, but I think the international export and import really exploded after the Korean War. You can’t really understand adoption without studying the geopolitical context.

But people — especially Christians, but even liberals and progressives and radicals…there’s such a resistance to that because the narrative, “These families were saved,” feeds so much into American exceptionalism and the idea that America is this noble country that goes around saving other countries. And it happens on the family and community level, as well.

So, there’s my individual story of how it happened, but to tell that story without the context of what was happening globally is dishonest. But that was how I understood my story for a long time: I thought I had been abandoned. I thought my Korean mother couldn’t take care of me. And really it was that she was oppressed. She was exploited, just like the baby Scoop era here. It’s the same thing.

I thought I had been abandoned. I thought my Korean mother couldn’t take care of me. And really it was that she was oppressed. She was exploited.

She was living out of wedlock with my Korean father. They had met in middle School, became friends, and eventually fell in love. They moved in together, and my Korean father got arrested and put in prison a month before I was born. In Korea in 1970s, and still in Korea in the 21st century, it’s like the Baby Scoop Era here in America where women have no rights. You have women in Korea who will unalive themselves because they undergo divorce.

She had no choice. Her older sister was like, “You’re leaving him. You can’t raise this baby. He’s not a good person.” She already had somebody picked out for my Omma [mother] to marry. My Omma gave birth to me, and I later found out that I was in the hospital with her for about 5 days because I had to be born by a C-section. She nursed me and took care of me for that first week, and then my Imo [aunt] was like, “Nope,” took me forcibly from my Korean mother, and brought me to this Christian agency.

In my mind, it’s like, OK, you have these missionaries setting up shop there, but if it was really based in what Christians are supposed to believe and practice, they would have helped all of these Korean women take care of their children. These types of stories…I’m well-connected to the adopted Korean community, and I know a lot of other Koreans who have reunited, and it’s different stories, but the same story all the time: oppressed and exploited mothers and fathers and families who are preyed upon and groomed and coerced to relinquish their children to feed the White saviors’ desire to purchase children and to be the savior.

That’s the individual story, but it’s reflective of the violence that adoption inflicts upon families and communities. And it is violence. This language is uncomfortable for so many people when you talk about adoption because adoption is framed as though it’s beautiful, it’s noble, it’s a good deed, it’s charitable. You’re saving these children, you’re giving them better lives. You’re showing them real love. It’s all of this language.

It’s different stories, but the same story all the time: oppressed and exploited mothers and fathers and families who are preyed upon and groomed and coerced to relinquish their children.

It truly is like the novel 1984. It really is propaganda. My Omma can barely look me in the eyes without bursting into tears every time. Same thing with my Imo, who forcibly removed me from my Omma’s arms. She has incredible regret. She can barely look me in the face because she knows what she did was awful.

I think we’re all a product of our culture. I’m a product of that, too. So I’m not saying that I’m above that, or…

KT: But if the system hadn’t been in place to make that the only option, everything would be different.

MK: Exactly. Prior to the war there, that wasn’t even a thing in Korea. And so I think it was the result of America exporting capitalism and all of that stuff — the churchianity, all of that — and bringing it to Korea. I hold Korea just as culpable — that’s what that paper I mentioned talks about, too — but they were trying to position themselves in this economic hierarchy, and the leaders at the time saw this as a very politically and economically expedient way to deal with what they saw as a problem.

Instead of these missionaries being like, “These poor women. Let’s help empower them. Let’s take care of them,” they were like, “Oh, they’re morally inferior, so we’re going to take their children.”

The children that were first sold and bought were often mixed race. They were the children of women who had been basically sold into the sex trade. The “comfort women” started with Japanese occupation and continued into the Korean War, and American GIs in Korea would go to, basically, these camp towns where young women, sometimes children, were forced to have sex with these soldiers.

Not surprisingly, they would become pregnant, and so instead of these missionaries being like, “These poor women. Let’s help empower them. Let’s take care of them,” they were like, “Oh, they’re morally inferior, so we’re going to take their children.”

That’s ultimately how it started. America helped create the problem, and then they’re like, “Oh, we can solve it.” There’s so many layers of wrong in that.

KT: Do you think there have been any improvements, or has there been reform, in the adoption industry since the time of your adoption?

MK: In the abolitionist community we talk a lot about how you can’t reform systems of harm. How do you “reform” family separation? How do you “reform” family policing? Is there an ethical way to separate families? Is there an ethical way to exploit women who are distressed and experiencing economic exploitation? Is there an ethical way to sell and buy children?

How do you “reform” family separation? Is there an ethical way to separate families? Is there an ethical way to buy and sell children?

Again, it’s this type of language — A lot of times people are like, “You’re radicalizing the language,” but it’s like, no, it feels that way because you’re so accustomed to the propaganda language. But when you pare it down, it’s literally the selling and buying of children. Literally! Those are just the facts.

Going back to your question of have things improved, not really. Yes in the sense that more people are being exposed to the truth, so in that sense it is improving, but again, I’m not about improving it. I’m about abolishing it.

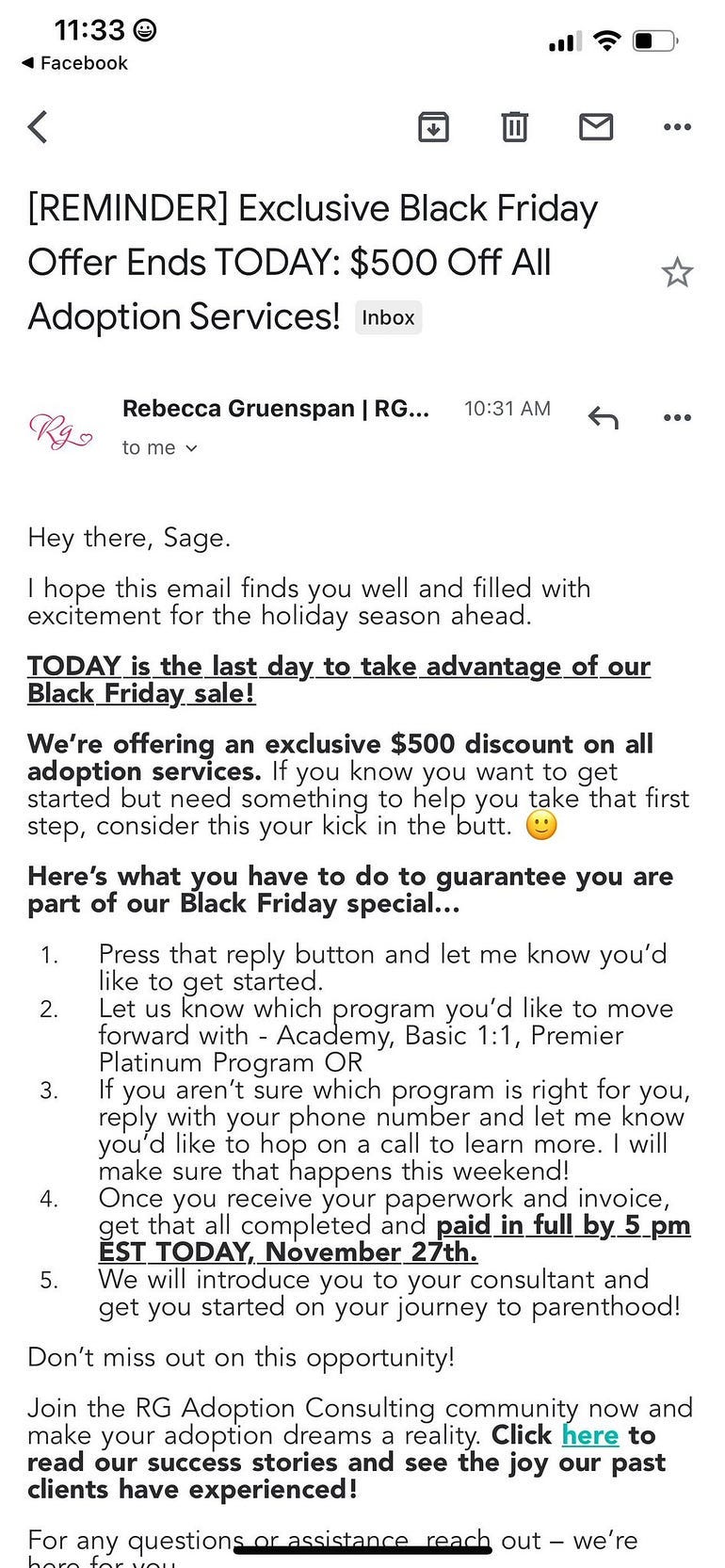

KT: Not long after I’d been directed to an adoption website that has babies priced for adoption depending on skin shade (the lighter the skin, the higher the price), I saw a screenshot of an email announcing a Black Friday adoption sale that you pinned to your X account. It’s all astounding.

MK: It’s sickening, right? It makes me feel emotional, because it’s just like –I know people don’t want to think about it, because when you really let it sink in, it’s devastating. It’s devastating.

Talking about it as somebody who’s directly impacted by it, it makes me feel bad, because, “Oh, yeah. I was just basically this commodity.” It doesn’t feel good. But that’s why we need to talk about it, because the truth is that’s why we are advocating for abolishing it.

It makes me feel bad, because, “Oh, yeah. I was just basically this commodity.” It doesn’t feel good. But that’s why we need to talk about it.

Now, people and their extreme thinking — and in wanting to discount us — are like, “You just want to let all the babies languish in foster care?” Of course not. Is adoption the only answer to family crisis? Is adoption the only answer to economic exploitation? If we’re not providing basic needs like housing and nutrition and healthcare and childcare, and how can we say we’re providing for these families the opportunities they need to care for themselves?

People are so narrow in their scope. This is all liberation work. Adoption has to be contextualized within the struggle for liberation, but people don’t view it that way.

There’s a podcast, upEND Movement. They’re not adopted people but are mainly social workers and people like that who are advocating for abolishing family policing. They’re asking the questions that need to be asked, which aren’t, “What about all the children who need families?” but “What about all the families who need support?” When talking to adoptees, it shouldn’t be, “Would you have rather grown up in an orphanage?” It should be, “Would you have rather grown up with your family? How could that have been made possible?”

We need those kinds of shifts in focus, in thinking, in the language we use, in the questions we ask.

KT: I wonder if part of the reason people don’t want to discuss adoption reform is that they think, “Well, this is a complicated, long-term issue, and we have children needing help right now.”

Is there an immediate alternative to adoption for the occasional children who simply cannot be with their parents?

MK: It is a rare occasion, the situation that you’re talking about. It’s rare that there’s not a living family member that can and wants to take care of those children. It’s usually an issue of resources and access.

Z, who does Adoptees Crossing Lines, and I talked about this. There are so many things someone can do. In that immediate situation, there are organizations. Connect that child with services that provide support.

It’s rare that there’s not a living family member that can and wants to take care of those children. It’s usually an issue of resources and access.

But, again, it’s such a rare situation, so the focus should be on organizations that help families. It shouldn’t be revolutionary that if you help people meet their needs, they’re able to take care of themselves and their families and their level of risk exponentially decreases. I think that people — again, part of it is just propaganda and that they’ve never been presented with other ideas — but people make it complicated. I’m not saying that it’s not, but if somebody wants to do something, it’s not hard to do something that contributes to family preservation.

It shouldn’t be revolutionary that if you help people meet their needs, they’re able to take care of themselves and their families.

Maybe it means supporting women who are in prison. Maybe it means supporting women who are in situations where there’s domestic violence. That’s why it’s important to have these discussions. At the root of family separation is economic injustice and social injustice. That’s where we have to approach the issues.

People want to say, “It’s because that mom is on drugs and doesn’t deserve to keep her child.” Well, help that mom get access to therapy and to healing instead of writing her off and thinking that the answer is to further traumatize her child and give her child another adverse child experience.

Adding more trauma to trauma is not going to help the child. And yes, it’s more complicated, and it’s more long-term, but that’s what we want to do. We want long term solutions. We don’t want to try to put a Band-Aid over an amputated leg. But that does mean investing our resources, money, time, and policy structures into building and creating those supports.

Adding more trauma to trauma is not going to help the child

I think it does require a lot of self reflection and it does require people dealing with their own pain, because I think if you’re going to be willing to acknowledge and show compassion toward people who are in pain, you have to be willing to deal with your own pain. And that’s much harder than judging someone and writing them off.

*This interview originally appeared in the Medium publication Fourth Wave.

Read the other stories in this series:

The “Loving Option” Is a Lie (how the language used by the adoption industry misleads the public and manipulates women into parting with their children)

Q&A: Why Adoptee Lina Vanegas Wants to Abolish Adoption: Money corrupts an industry claiming to help vulnerable kids

Q&A: Birth Mother Renee Gelin Says Family Preservation *Is* Adoption Reform: But there’s no money to be made in family preservation